The great horned owl is one of the most powerful and adaptable birds of prey found in the Americas. Easily recognized by its large size, piercing yellow eyes, and prominent ear tufts, this owl thrives in forests, deserts, wetlands, grasslands, and even busy urban areas. Known for its deep, echoing hoot and extraordinary hunting abilities, the great horned owl sits near the top of the nighttime food chain. Learning about its appearance, habitat, behavior, and survival strategies reveals why this species is often called the “tiger of the sky.”

Species Overview and Scientific Classification

The great horned owl belongs to the genus Bubo and the scientific name Bubo virginianus. It is part of the true owl family, Strigidae, which includes many of the world’s most powerful nocturnal predators. The name “great horned” comes from the feather tufts on its head, which resemble horns but are not ears. These tufts are believed to play a role in camouflage and communication rather than hearing.

This owl is considered one of the most successful raptors in the Western Hemisphere. Its ability to live in nearly every type of environment, combined with a broad diet and strong territorial instincts, has allowed it to thrive from the Arctic tree line to the tropical rainforests of South America. Because it sits high on the food chain, the great horned owl plays a major role in maintaining natural population balance.

Geographic Range and Natural Distribution

Continental Range

The great horned owl has one of the widest distributions of any owl species. It is found throughout most of North America, including Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Its range continues through Central America and extends across much of South America, reaching countries such as Colombia, Brazil, Peru, Argentina, and Chile. Few birds of prey occupy such a vast and diverse territory.

This widespread range means the species has developed regional variations in size, coloration, and behavior. Northern populations tend to be larger and heavier, while tropical individuals are often smaller and darker. Despite these differences, all great horned owls share the same powerful build and distinctive facial features.

Climate and Elevation Tolerance

Great horned owls are exceptionally tolerant of climate extremes. They inhabit cold boreal forests, scorching deserts, humid swamps, and temperate farmlands. They can live at sea level along coastlines or high in mountainous regions where snow covers the ground for much of the year.

This adaptability is one reason the species has remained stable while many other birds face habitat loss. Whether in wilderness areas or near human settlements, great horned owls are capable of finding shelter, nesting sites, and abundant prey.

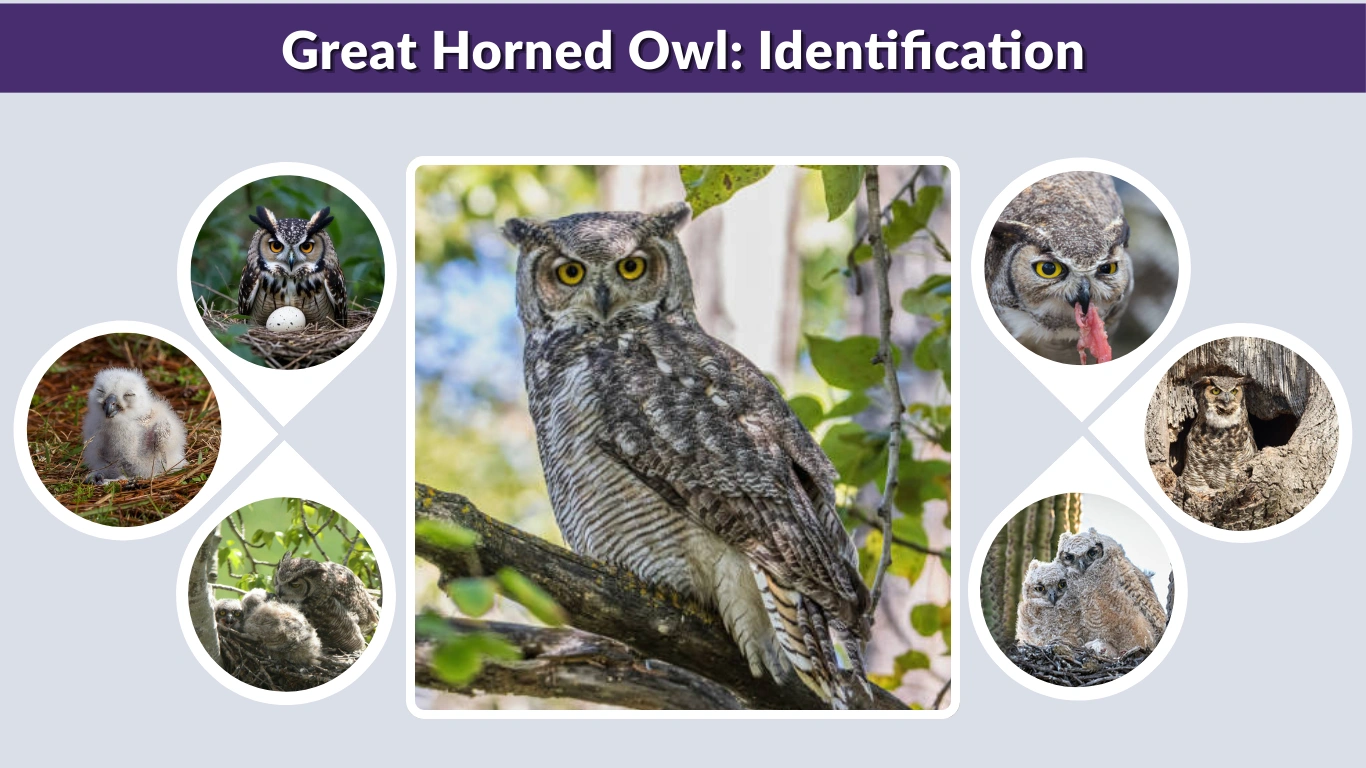

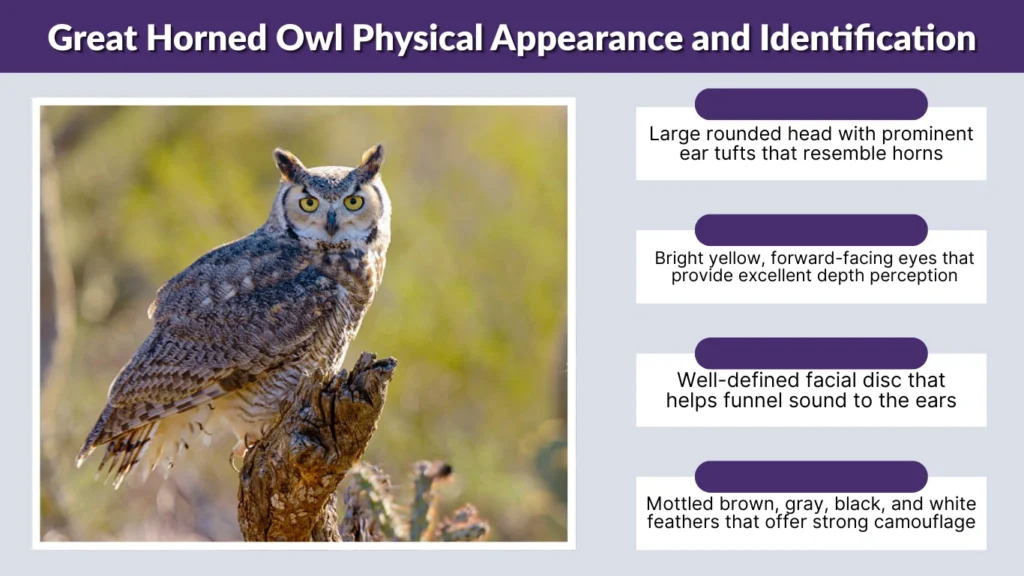

Physical Appearance and Identification

The great horned owl is instantly recognizable, even among other large owls. Its appearance reflects both strength and stealth, perfectly suited for a life of nighttime hunting.

- Large rounded head with prominent ear tufts that resemble horns

- Bright yellow, forward-facing eyes that provide excellent depth perception

- Well-defined facial disc that helps funnel sound to the ears

- Mottled brown, gray, black, and white feathers that offer strong camouflage

- Thick, heavily feathered legs that protect against cold and struggling prey

- Massive talons and a sharply hooked beak designed for gripping and tearing

The body is bulky and muscular, giving the owl a powerful silhouette when perched. Its broad wings allow nearly silent flight, while its feather patterns blend seamlessly with tree bark, rocks, and shadows. When resting, the great horned owl often sits upright and still, relying on camouflage rather than movement to avoid detection.

Size, Wingspan, and Weight Characteristics

The great horned owl is one of the largest owls in the Americas. Adults typically measure between 18 and 25 inches in length, making them similar in size to a large hawk. Their wingspan usually ranges from 3.3 to 4.8 feet, allowing for strong, controlled flight over open landscapes and forest edges.

Weight varies by region and sex. Females are noticeably larger and heavier than males, a common trait among birds of prey. A female may weigh over 4 pounds, while males are often closer to 2.5 to 3 pounds. This size difference helps females defend nests and manage larger prey, while males are often more agile hunters.

Their large wings, thick muscles, and dense bones contribute to remarkable lifting power. Great horned owls can capture and carry animals nearly equal to their own weight. This physical dominance supports their reputation as one of the most formidable nocturnal predators.

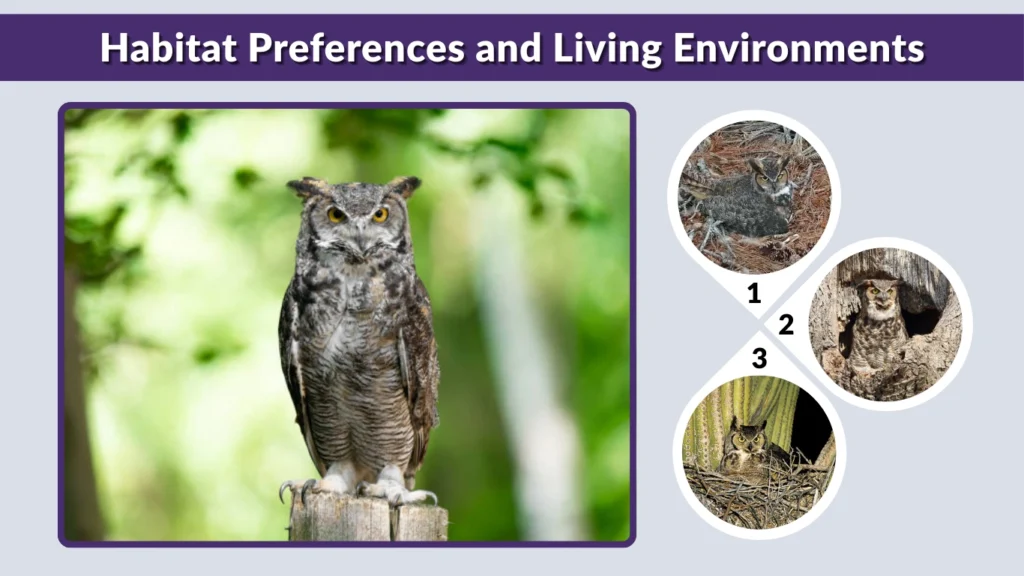

Habitat Preferences and Living Environments

Common Habitat Types

Great horned owls are not limited to a single ecosystem. They are found in dense forests, open woodlands, grasslands, marshes, deserts, agricultural fields, and river valleys. They frequently live near forest edges where trees meet open hunting grounds, providing both shelter and access to prey.

In recent decades, they have become increasingly common in suburban and urban environments. Parks, cemeteries, golf courses, and large gardens can all provide suitable roosting and nesting areas. Their willingness to live near humans demonstrates exceptional ecological flexibility.

Roosting and Shelter Sites

During the day, great horned owls rest in sheltered locations such as thick tree branches, cliff ledges, dense foliage, or abandoned buildings. They prefer secluded spots that offer shade and concealment. These resting sites protect them from harsh weather and from being harassed by smaller birds that often mob owls during daylight hours.

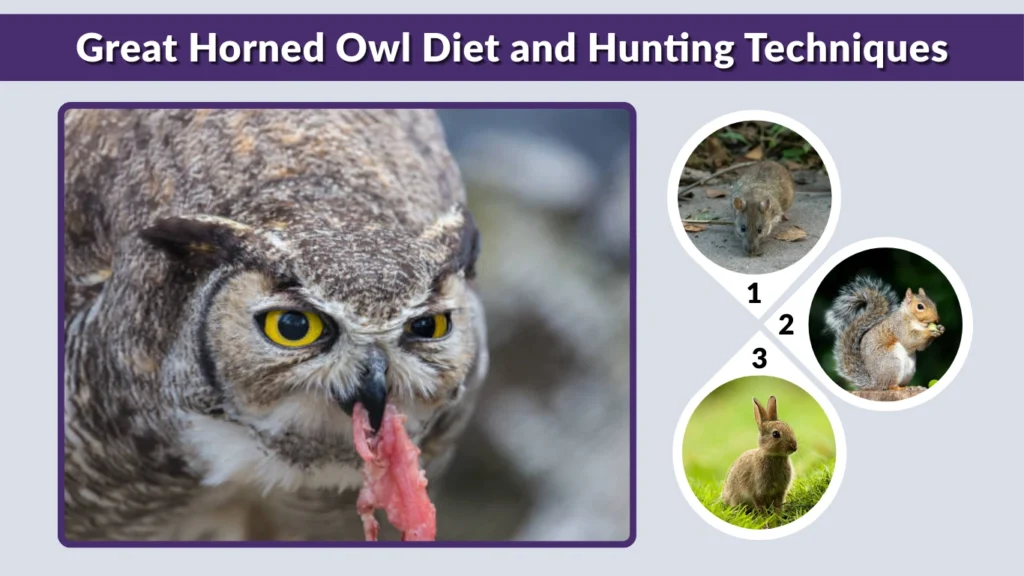

Diet and Hunting Techniques

The great horned owl is a true apex predator, capable of hunting a remarkable variety of animals. Its success comes from a combination of silent flight, powerful vision, sensitive hearing, and crushing talons. Unlike many specialized predators, this owl is an opportunistic feeder, adjusting its diet based on season, location, and prey availability.

- Rodents such as mice, rats, squirrels, and voles

- Rabbits and other medium-sized mammals

- Birds including ducks, geese, crows, and even other owls

- Reptiles and amphibians like snakes, lizards, and frogs

- Large insects and other invertebrates

- Occasional fish and carrion when live prey is scarce

Great horned owls usually hunt from a perch, scanning the ground with intense focus. Once prey is located, the owl swoops down in near silence, striking with incredible speed. Its talons can exert immense pressure, often killing prey instantly. If necessary, it will carry the animal to a nearby perch before feeding. This hunting style allows it to dominate a wide range of habitats.

Behavior and Daily Activity Patterns

Nocturnal Lifestyle

Great horned owls are primarily nocturnal, becoming most active from dusk until dawn. Their large eyes are specially adapted for low-light vision, allowing them to detect even slight movement in near darkness. While they cannot move their eyes within their sockets, they can rotate their heads up to about 270 degrees, expanding their field of view without shifting their bodies.

Their hearing is equally impressive. Ears positioned at slightly different heights allow them to pinpoint sounds with extreme accuracy. Combined with silent wing feathers, this makes them deadly nighttime hunters. Although mainly nocturnal, they may occasionally hunt during cloudy days or early mornings.

Territorial and Solitary Nature

These owls are highly territorial, especially during breeding season. A mated pair may defend a large hunting territory, warning intruders with loud hoots and aggressive displays. Outside the breeding period, great horned owls are mostly solitary, coming together only to mate.

When threatened, they may spread their wings, puff up their feathers, and snap their beaks. If nests are approached, adults can dive toward intruders in a defensive swoop, though serious attacks on humans are rare.

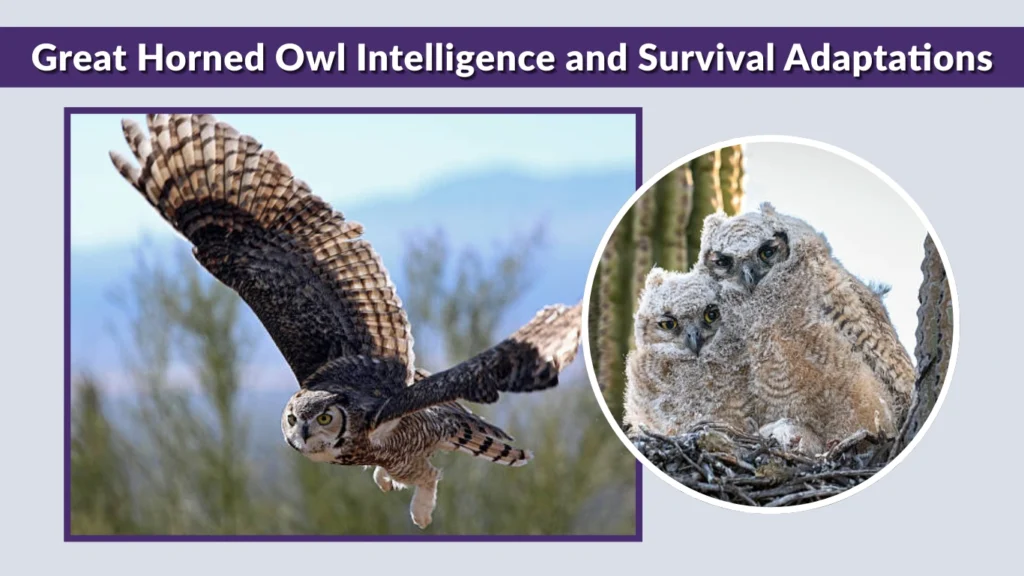

Intelligence and Survival Adaptations

Great horned owls possess a collection of adaptations that make them extraordinarily successful. Their wing feathers have soft, fringed edges that break up airflow, producing nearly silent flight. This allows them to surprise prey before it can react.

Their powerful legs and feet are among the strongest of any raptor. A locking tendon mechanism enables them to maintain a crushing grip without constant muscular effort. Thick plumage protects them from cold climates and from bites or scratches when subduing prey.

Camouflage also plays a major role in survival. The mottled coloring of their feathers closely resembles tree bark, helping them remain unnoticed while roosting. Their ability to adapt to human-altered landscapes, including farmland and cities, further increases their chances of long-term survival.

Breeding Season and Courtship Behavior

Mating Displays and Vocalizations

Courtship often begins in late fall or early winter. Males advertise territory and attract mates with deep, rhythmic hoots that can carry for miles. Pairs may engage in duets, bowing, and mutual calling. Once bonded, pairs often remain together for many years.

These vocal displays serve both to strengthen pair bonds and to warn rival owls to stay away. The great horned owl is among the earliest nesting birds in North America, sometimes laying eggs while snow still covers the ground.

Nest Site Selection

Rather than building their own nests, great horned owls usually take over abandoned nests from hawks, eagles, herons, or crows. They may also nest in tree cavities, cliff ledges, or on man-made structures. This flexibility allows them to breed successfully in many environments.

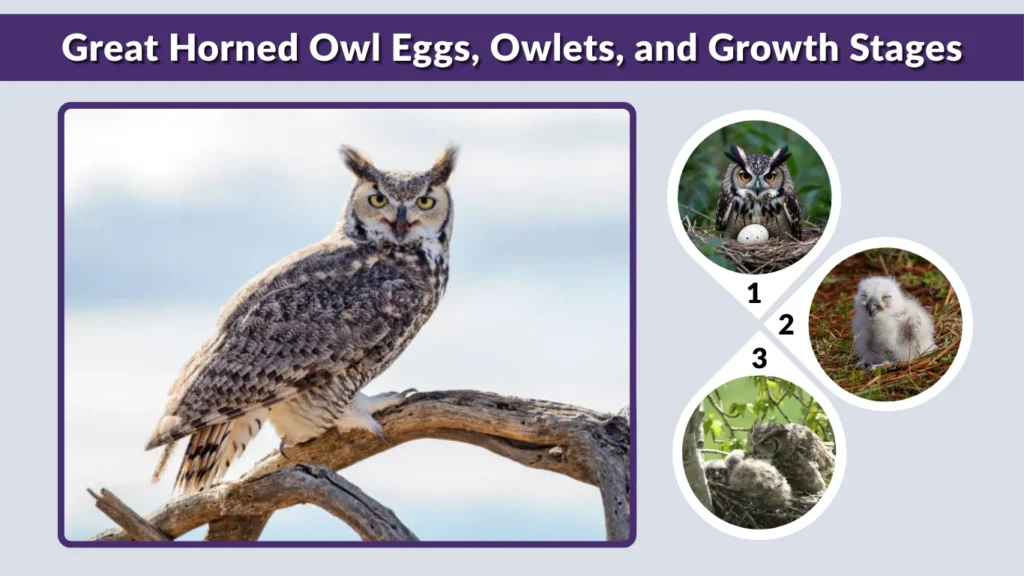

Eggs, Owlets, and Growth Stages

Females typically lay one to four eggs, with two being most common. Incubation lasts about 30 to 35 days and is performed mainly by the female, while the male provides food. The owlets hatch covered in soft down and are completely dependent on their parents.

As they grow, the young develop feathers, open their eyes fully, and begin exercising their wings. After about six weeks, they leave the nest but remain nearby, a stage known as “branching.” During this time, parents continue feeding and protecting them. Full independence usually occurs after several months, once hunting skills improve.

Calls, Sounds, and Communication

Great horned owls are famous for their deep, resonant hoots. These sounds serve as powerful tools for communication across large territories.

- Low, rhythmic hoots used to mark territory

- Courtship calls exchanged between mates

- High-pitched begging sounds from juveniles

- Sharp barks, hisses, and screeches as alarm calls

- Soft clucks and whistles between parents and owlets

Each vocalization carries specific meaning, from attraction and bonding to warnings and defense.

Lifespan, Mortality, and Natural Threats

In the wild, great horned owls commonly live 10 to 15 years, though some survive much longer. In captivity, where food and medical care are provided, individuals may exceed 25 years.

Young owls face the greatest danger. Predators, starvation, and harsh weather cause high mortality in the first year. Adults have few natural enemies, but they may be injured by vehicles, power lines, poisoning, or habitat destruction. Despite these risks, the species remains widespread and relatively stable.

Ecological Importance and Role in Nature

Great horned owls play a crucial role in controlling populations of rodents and other small animals. By keeping prey numbers balanced, they help protect crops, forests, and grasslands from overpopulation damage. They also influence the behavior and distribution of other predators, shaping entire ecosystems.

Because they are sensitive to environmental toxins, changes in great horned owl populations can reflect broader ecosystem health. Their presence often indicates a functioning and balanced natural environment.

Relationship With Humans and Cultural Significance

Across cultures, the great horned owl has been associated with wisdom, mystery, and power. Indigenous traditions often viewed it as a spiritual messenger, while modern society recognizes it as a symbol of wilderness and nighttime strength.

In cities and farms, these owls can benefit humans by reducing rodent populations. Misunderstandings sometimes lead to fear, but great horned owls are generally shy and avoid direct contact. Conservation efforts now focus on protecting habitats and educating communities about peaceful coexistence.

FAQs

How big is a great horned owl compared to other owls?

The great horned owl is one of the largest owls in the Americas. It is much bigger than screech owls and barn owls, with a wingspan that can approach five feet. Only a few species, such as the snowy owl and Eurasian eagle-owl, rival it in overall size.

What animals do great horned owls eat most often?

Their diet mainly includes rodents, rabbits, and birds, but they are highly opportunistic. Depending on location, they may also eat reptiles, amphibians, insects, and fish. This flexible feeding strategy allows them to survive in deserts, forests, wetlands, and urban areas.

Where do great horned owls usually nest?

Great horned owls rarely build nests. They prefer to use abandoned nests made by hawks or other large birds. They may also nest in tree cavities, cliffs, or on buildings, showing remarkable adaptability in choosing breeding sites.

Are great horned owls dangerous to people or pets?

They are not aggressive toward humans and usually avoid contact. However, during nesting season, adults may defend their territory if someone approaches too closely. Attacks are rare and usually meant to scare intruders away rather than cause serious harm.

How long can a great horned owl live?

In natural conditions, many live between 10 and 15 years. Some individuals survive longer, especially in protected areas. In captivity, with regular care and food, great horned owls may live more than 25 years.